Hans Zimmer: Learning the Craft of Sound | ||

|

Audiohead | ||

|

From Numbers to Notes Growing up in Germany, Hans Zimmer received very little formal training to prepare him for his future as one of the top film composers in the world. “I must have had about two weeks of piano lessons,” he says, joking.  But he made up for his lack of experience with his knowledge of

technology and computers. “I was making music on computers a couple

years before IBM invented the first PC,” he says, reminiscing.

“It would take forever to input a string of numbers into it just to

get a couple notes to come out.

But he made up for his lack of experience with his knowledge of

technology and computers. “I was making music on computers a couple

years before IBM invented the first PC,” he says, reminiscing.

“It would take forever to input a string of numbers into it just to

get a couple notes to come out.“I felt that playing with computers was preferable to practicing the piano,” he jokes. “I was in my late teens, early twenties. I had a Roland Microcomposer MC8 which had 16K of memory. That was really something then. After that, I used the Fairlight. And nobody could take classes in this stuff because they just didn’t exist. “Today, it’s amazing what you can do on a PowerBook,” he says. “It’s a more democratic system again. You don’t have to have hundreds of thousands of dollars. You just need to have some good ideas and be able to put them into action. And you have to have talent and musicianship.” Soon he was working on various rock & roll projects. “We ruined generations of kids,” he laughs, “and we tortured real musicians because our sense of timekeeping was very different — we were very much governed by electronic computers.” Avant Garde Defined In the 1980s, Zimmer became an assistant to film composer Stanley Myers in London. “Stanley knew everything about the orchestra,” says Zimmer. “He’d done ‘The Deer Hunter’ and he was working with really avant garde filmmakers in England. You can only be truly be avant garde if you have no money to make a movie,” he says, laughing. “You can only be truly be avant garde if you have no money to make a movie,” he says, laughing. Myers wanted to work with somebody who understood the electronic world, and Zimmer fit that bill perfectly. “And so I learned about orchestras from him,” Zimmer says. They collaborated on a couple of films together, including “My Beautiful Launderette,” which inspired a series of new movies in London. “I think that ‘Snatch’ and all those new English movies sort of came out of that wave,” says Zimmer. “I wanted to work in Hollywood. But I’d promised myself that I wasn’t going to come to the U.S. unless I was asked to do a job, because I knew I’d make a terrible waiter,” he adds. Scoring “Rain Man” Then one day, director Barry Levinson offered him the chance to score “Rain Man,” so Zimmer made his move to the States. “I did ‘Rain Man’ the way I did all my European films. I didn’t really do it in the studio — I just set up my Fairlight in Barry’s office with a couple more toys and gadgets,” he explains.

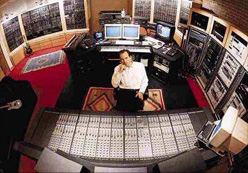

“So we fumbled our way through that score and I thought that was the end of my Hollywood career,” he says, smiling. “But I think every movie I do must mean the end of my career. So, I just keep doing them and forgetting the pain of the last one. I’m still just getting started. I’ve seen glimpses that I might actually get good at this!” After 12 years in the U.S., Zimmer has finally decided he’s here for good. But he also works in Europe frequently because “You can bring back different ideas. You can’t get stuck in one place.” Mentoring Composers Zimmer insists that mentorship is essential for developing good craftsmanship. Bothered by how other composers in the U.S. didn’t seem open to sharing the trade with knowledge-hungry budding composers, Zimmer and his business partner, Jay Rifkin, started up Media Ventures, a composing compound where newcomers could develop good craftsmanship. “When I was in England, Stanley Myers was very encouraging and he got me movies. When I came to America, that sense of apprenticeship didn’t really exist. People helping other people further their careers didn’t really exist,” reflects Zimmer. “Everybody was doing their thing and wouldn’t let any new people in. “But if you look at the top composers these days — John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein — most of them are in their 70s,” he points out. “So I always think that in order for something to survive, there needs to be something biting at its heels. It needs to be young and feisty.” Next page: The Language of Film |

|

|

|